Between Before and After, a solo show at Arroniz Arte Contemporáneo in Mexico City, 2018.

Slow

Light

Breaks

The complexly faded pages on the wall speak to us from another world, or rather a continuum of worlds. They were culled from a ledger book produced in 1875 by Printemps, the Parisian department store, at a time when this grand magasin’s use of elevators was a novelty, its departments still lit by gas, its use of fixed prices rather than haggling revolutionary. That’s 143 years ago now, a couple of lifetimes. Back then, the denizens of the Third Republic’s ascendant middle class would have been browsing folios for textile samples: more rich detailing for drawing rooms filled with plush furnishings and finely curved wood, with no idea that by 1947, halfway from then to now, clean-lined and detail-free modernism would have rendered that aesthetic obsolete and two world wars would have destroyed much else. With no idea that, between 1947 and now, the middle class would shrink again and dark forces thought vanquished at the end of World War Two would once more be rising.

The sample book is still around, though, recording time’s passage in an eerie way. These pages—some 20 of which Justin Hibbs acquired from a textile designer who had used the volume as an evocative portfolio for her own work—have discoloured to pinkish brown in a long chain of intermittent daylight, and, lacking what was once upon them, they unknowingly trace the cultural evolution of modernity into modernism’s hard-edged geometry. The missing swatches leave ghostly arrangements of rectangles and triangles on the paper, formerly negative space now turned positive, removal as addition. Sometimes the ad-hoc compositions look uncannily like works by Mark Rothko—just reaching artistic maturity in ’47—or Agnes Martin, or Josef or Anni Albers. On seven occasions here, Hibbs has intervened beyond presenting temporal readymades, adding more geometry that is newer if not new: cut-out blocks of pure, lithograph-printed colour from a Phillips auction house catalogue of twentieth-century design and furniture, the modernist present already in the past, the salient reference point swinging closer to Ellsworth Kelly.

These collages, rooted in the nineteenth century and augmented by the twentieth, are modulated by the ominous light of the twenty-first. As such they bracket a period of belief in progress, a feeling in recession today with all the talk of reverting to medieval times, subjective belief, localism rather than globalism, the dismantling of continent-wide projects that have ensured some semblance of peacetime. This progress, nevertheless, was bumpy, and involved a passage through clean-lined rationality (the pivot point of Hibbs’ implicit timeline, and the aspect his art most strongly recalls) that did not, in retrospect, transform humanity in its image, did not expunge the messiness and irrationality of our kind, did not successfully factor in its tenacity. In modernist art of the twentieth century, of course, there were claims to autonomy—and to the ‘destiny’ of media, painting for example becoming more and more itself—that we can barely process today. Hibbs’ works, appropriately, refute autonomy on various levels. Media-blurry, they are paintings without being paintings, partly painted by slow light. They find the artist not as controlling master of the scene but as collaborator with chance. They exist emphatically in time, whereas part of the goal of modernist art—exemplified by increasingly abstract artworks but also by the white-cube setting—was to suspend time. And they do not necessarily expect tomorrow to be better than today, though they contribute to a project of illuminating past behaviour that feels hopeful.

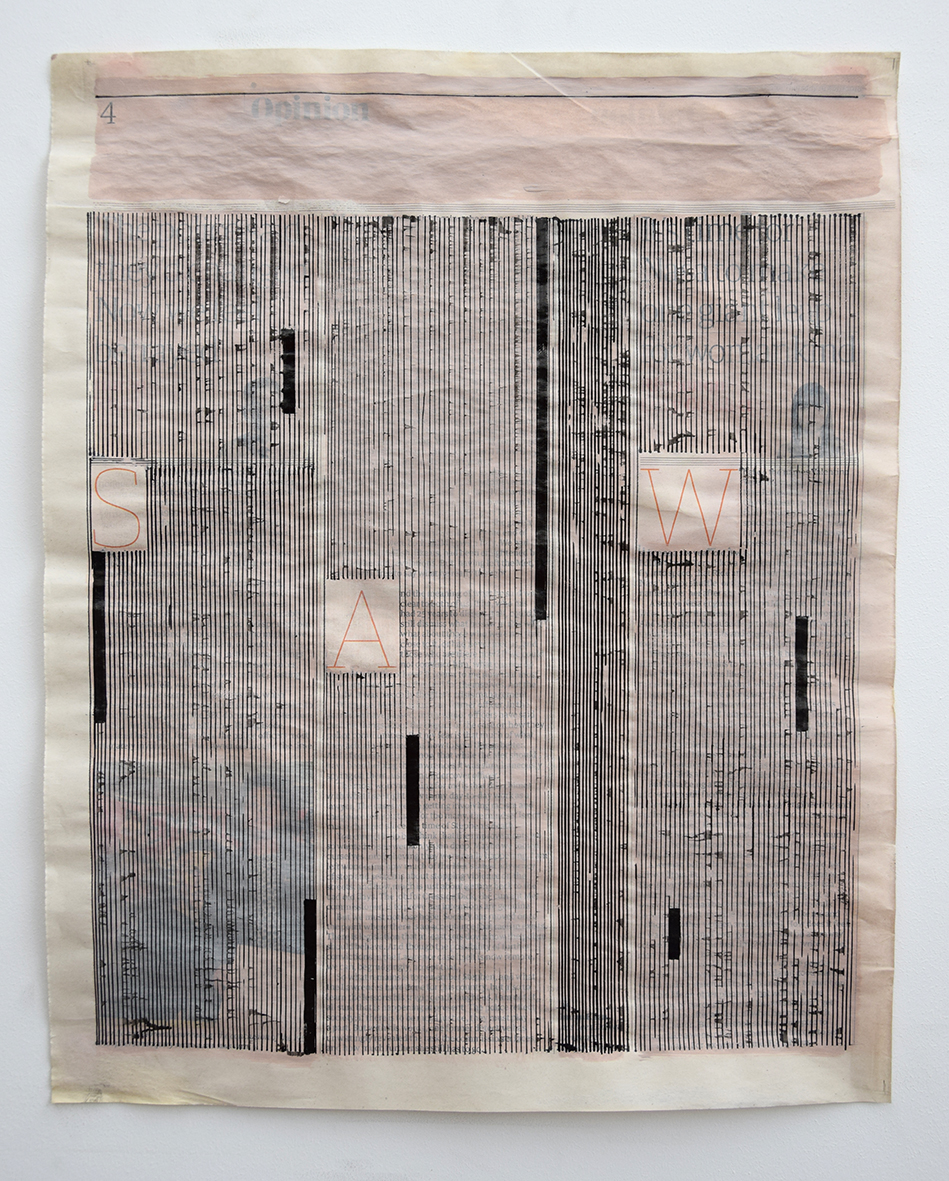

A second body of work here, meanwhile, exists on rather younger paper: recent newspapers, frequently the Financial Times, elsewhere The Guardian and The Times. Hibbs, like the rest of us in these tumultuous days, has become some kind of news addict, cast into a sea of opinion and ever-updating bulletins on a world where hard-edged truth is ever harder to come by. The British newspapers since 2016 have been dominated by Brexit, a statistical unknown whose status shifts daily, as does that of the other linchpin of contemporary news, the benighted American presidency. The cry of the Brexiteers was ‘take back control’—a statement synonymous with modernism, and for which the results are already in. On some level, taking back control is what Hibbs is doing here in collaborating with the newspaper layouts, using them as the ground for subjective geometric abstractions in ink and paint. Photographs turn ghostly under fine verticals. The slant of a headline becomes a springboard for radiating lines. Battalions of nested black stripes, like fragmentary ghosts of an Albers or an early Frank Stella, take up residence on the rumpled page.

Yet the works sit between anxiety and self-soothing—Hibbs is only halfway restoring control, even as the works seek the reassurance of Euclidean form, because he’s forced to deal with what’s already on the page. He’s cooperating with chance, accepting reality as an opportunity and something that can’t be fully wiped out, rather than seeking bloody-mindedly to push wholly against it. In that respect his geometry operates at a sanguine distance from that of the modern, which sought to act as if the messy real world didn’t exist, could be erased. This outlook extends, meanwhile, to his freestanding sculptures, which look sleekly modern in some ways but are double-faced—they have the air of steely origami, entraining both positive and negative space, and they’re mirrored so that, as the viewer moves around them, she or he appears in reflection, puncturing the work’s sovereignty. You—and your attitudes, anxieties, imperfections, changeability—are in there too, unstably so, as is the work on the walls surrounding the sculpture. It is, in this respect, the same dynamic animating the newspaper works, where the world implacably pokes through as a counterpoint: crypto, luxury, male rage, weaponry.

The newspaper works are pinked and browned like those on the ledger pages, the twin series conversing with and leaning on each other. The Financial Times is already pink, but Hibbs has tinted his fragile paper surfaces with paint. They look pre-aged, so that the gap collapses between 1875 and 2018. In both eras, hard-edged geometry feels out of time; we, and our forerunners, seek comfort in an accelerating age. Everyone who browsed the Printemps ledger—when that’s what it was—died with no inkling of what the whole century-and-change would bring, while between then and now lays an era in which we thought, hubristically, that we could overcome chance and history, tame the darker and more chaotic aspects of human nature. Modernism, now the stuff of auction catalogues, was nevertheless merely a subset of modernity, which is still with us and has given us, over time and inter alia, electric lights, elevators, computers, the Internet, social media, allegedly hacked elections. Modernity displaces as much as it creates, driving good out in the service of progress: print media, printed newspapers for example, is hanging on by a thread. Whether progress really leads us forward or whether we’ve confused progress with technological advancement is another question.

Meanwhile, five years ago, Printemps, which focuses as ever on luxury goods for those who can afford it, was bought by a Qatari-controlled investment fund that enjoys profitable tax loopholes. These faded pages have been there through all of this, through all these worlds. If one wished they could speak, well, now they do.

Martin Herbert

Click through Slideshow above of Installation Images

Below: Works from ‘The Observer’ series, Ink on Newspaper pages, all works 2018